Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

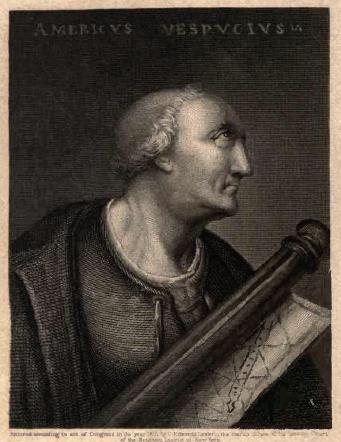

Florentine explorer and

cartographer, two of his famous letters (b.1451-d.1512)

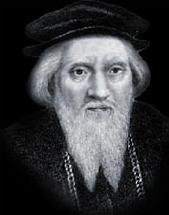

Amerigo Vespucci as a famous navigator in Spain, looking up to the

stars which guided him, from an engraving made after a painting

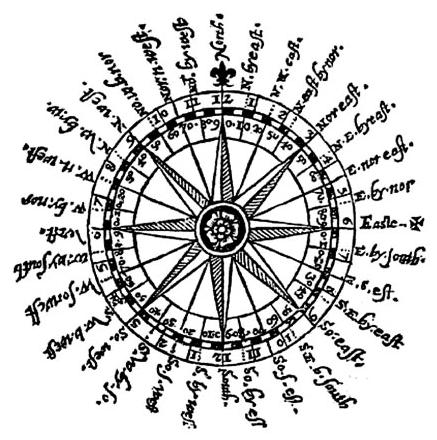

purportedly by the famous Florentine painter Bronzino Mariner's Compass

Dial

"It is worthy of remark, that while all the prominent powers of

Europe availed themselves of the services of Italian navigators in

prosecuting the discovery of new regions, and in acquiring new

possessions; not a foot of territory was obtained by any of the

governments of that country. 'The skill in nautical science, which the citizens of her republics

had acquired, in the course of a long and prosperous career of

mercantile enterprise, was rendered entirely useless to them by the

petty feuds and factions which occupied the attention of their rulers. 'Venice, Genoa, Florence, and Pisa, though fully awake to the

importance of the undertakings which were in progress, and sensible that

their success would inevitably be the beginning of ruin to their own

commerce, were yet so much engrossed in the unfortunate conflicts of the

times, they heeded not the warnings which occasionally reached them."

Lester from The Life and Voyages of Americus Vespucius,

1853. King Ferdinand of Spain "The dominions of Ferdinand and Isabella just then [1490] afforded a

fine field for profit in merchandise. The splendid court of those

illustrious sovereigns, and the wars they had for a long time prosecuted

against the Moors, had drawn from all quarters of Europe large numbers

of chivalrous young nobility of the age, who were anxious to gain

reputation and military experience on the field of battle, and regarded

the contest with the infidels on the hills of Grenada, in the light of

another Christian crusade. 'Italian merchants and bankers were not backward in taking advantage

of the wants occasioned by this great influx of foreigners, and such

extensive military movements. A great many of them were to be

found in all parts of the Peninsula..." One was to become

Amerigo's associate, Juan [Giovanni] Barnardi.

Lester from The Life and Voyages of Americus Vespucius, 1853

Queen Isabella of Spain Giovanni Caboto In June, 1497, Giovanni Caboto (he was a Venetian citizen) and his English crew landed in

Newfoundland, Canada, after sailing from Bristol, England, via Ireland

and then a northerly route. They returned to England safely and

were feted. Caboto set out again in 1498 with more ships but was

never heard from again. In 1005, or so, the Icelander Viking Leif Ericson and his sailors

settled the northern tip of Newfoundland and called their settlement

Vinland. "An Italian woman named Elena Vespucci, bearing

proofs of her lineal descent from the famous navigator, came to America

a few years ago, and made application to our Congress for a grant of

land, on account of her relationship to the Florentine from whom our

continent derived its name. Subsequently, her brother and two sisters,

Amerigo, Eliza, and Teresa Vespucci, made a similar petition to

Congress. They mention the fact that Elena, "possessing a disposition

somewhat indocile and unmanageable, absented herself from her father’s

house, and proceeded to London. Hence she crossed the ocean, and landed

upon the shores of Brazil, at Rio Janeiro. From that city she proceeded

to Washington, the capital of the United States." Elena Vespucci was

treated with respect. Possessed of youth and beauty, she attracted much

attention at the metropolis, but the prayer in the petition of both

herself and her family was denied. She was living at Ogdensburgh, New

York, when I visited that place in 1848." Lossing, from

Fieldbook of the Revolution, 1850

Elena scandalized the locals and society by living

with a man, Parish, out of wedlock. She may have been already wed

in Europe, so to avoid bigamy, she and Parish never married. When

she neared the age of 60, he paid her to move to Paris on her own, and

promised her an allowance (alimony of sorts). Nothing more is

known of Elena Vespucci after that time. Modern accounts of her

story are most often written by men, based on writing by men in the

past. They are largely negative, slanderous, and generally unkind.

Elena was an adventurous, independent minded woman, with modern sexual

sensibilities, who used her looks and sophistication to gain financial

support, attention, and a life-partner. The rest of her family

died in near poverty in Florence.

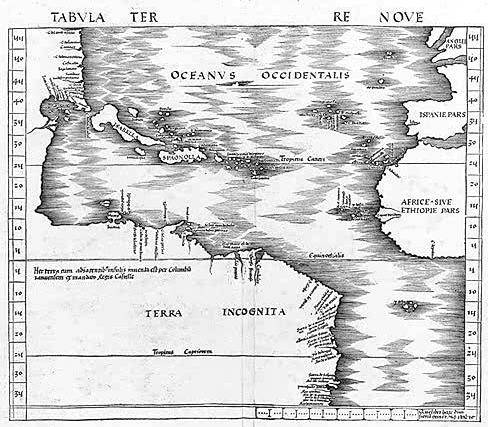

The voyages of Christopher Columbus, John

Cabot, and Amerigo Vespucci dramatically changed the world map. One of

the earliest printed maps to incorporate this new world view was

Johann

Ruysch's map which is found in the 1507 reprinting of the 1490 Rome

edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, both of which are

represented in the division. It is believed that Ruysch, a native of

Antwerp, accompanied Bristol seamen on a voyage to the great fishing

banks off the coast of Newfoundland in about 1500. (Atlas

Collection, U. S. Library of Congress)

Martin Waldseemuller. Cosmographiae introductio [St. Die,

1507]. This collective work of the group around Waldseemuller

contains the famous suggestion that the New World be named "America" for

Amerigo Vespucci, as well as an account of Vespucci's voyages that

credits Columbus with discovery. (John Boyd Thacher Collection) This was fortunate, because changing political and territorial

situations in the Near East meant that overland trade caravans were

too risky for traders. Water routes were sought to go to the

rich Eastern India and China.

Mariner's Astrolabe With maps, trade routes were scouted and trade encampments

established around Africa, thanks to the voyages of the Portuguese

Bartholomew Diaz in 1486, for the Portuguese crown. Columbus conducted trade and discovery voyages to the New World,

North and Central America, from 1492 onward, for the Spanish crown. Many other explorers traveled out, sponsored by the French and

English crowns too, and later by private corporations. Some

went forth with a benediction from the Pope. Luckily for us, these voyages coincided with the birth of the

printing press, and a new literary age, when writers set out to

document the events of their age in letters, pamphlets and books, as

did Amerigo Vespucci.

Vespucci grew up in Florence when she was the center of the New

Learning: the Liberal Arts and Classical education that was inspired

by ancient Greek and Arab texts. Amerigo had a strong grasp of

Latin, geometry, mathematics, classical history, cosmography, and

had even met the famous cosmographer Toscanelli.

Amerigo Vespucci as a young man in Florence Amerigo grew up a contemporary of Lorenzo (the Magnificent) de'

Medici, and of Piero Soderini, who would later rise to rule

Florence. Soderini would receive letters from his childhood friend, Amerigo,

about Vespucci's travels. In 1490, Amerigo went to Spain to make his business fortune.

His family had suffered a financial setback, so his efforts were

needed. He left Florence specifically as an agent for Lorenzo

di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, to take care of some pressing business

interests Lorenzo had in Spain.

Lorenzo was Lorenzo the Magnificent's

young cousin, educated along with Lorenzo's still younger children,

and was later a rival of Lorenzo's son, Pietro, for head of the

Medici family interests when Lorenzo the Magnificent died. Amerigo traveled to Spain with his younger cousin, Giovanni, who

later accompanied him on all his voyages, and learned the skill of

navigation from his older cousin. Giovanni was purported to be a

witty young man who was good company, an important trait for sailors

in any era. Amerigo also escorted to Spain many children of

Florentine nobles, who were sent there solely for the adventure and experience of travel. Once in Spain, Amerigo worked as a business agent for Florentine

families. He worked together with another agent, Donato Niccollini. But by 1492, Amerigo was working with Juan Bernardi, who was soon

after contracted by the King and Queen of Spain to equip and

maintain a fleet of four ships that were to sail back and forth

between Spain and the New World, or the Indies, as it was then

believed. That's how Amerigo became the agent who equipped Columbus's fleet. Around 1495, Amerigo met Christopher Columbus (Admiral Colon),

and the two were said to have discussed their differing theories

about what Columbus had discovered on his voyage. Columbus

believed he had seen territory belonging to the Great Khan of Asia,

while Vespucci believed Columbus had discovered a new continent that

existed somewhere between the Atlantic and the Indian oceans. Columbus was a well-read and superstitious man. But

Vespucci was a well-studied man who was schooled in the new Liberal

Arts, which centered around man and science, not God nor

superstition. So it is no surprise that Vespucci's version of

the truth was the most accurate.

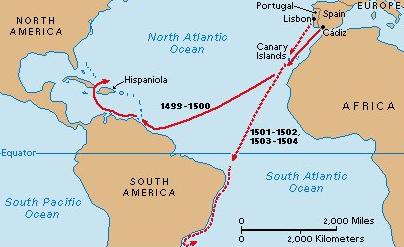

In 1497 Amerigo Vespucci set sail with a private expedition to

the New World as a representative of the Spanish crown.

Private expeditions were allowed under a General License issued by

the Spanish crown, much to the annoyance of Columbus. Vespucci

proved to be an accomplished navigator, and chronicler of their

adventures. In 1498, Columbus, after much frustrating delay, set sail on his

third voyage to the New World (the Western Ocean, as Amerigo calls

it). Amerigo made a second voyage to the New World for the Spanish

crown in 1499, together with Columbus's son, Don Diego. There were a third and fourth voyage by Amerigo Vespucci made in

and after 1501 for the King of Portugal to South America (to the

South Seas, as Amerigo calls it).

Amerigo Vespucci was a famous letter-writer,

and his letters to his one-time employer, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco

de' Medici and friend Soderini are his most famous. But

it should be understood, that Amerigo wrote his accounts of his

voyages, and then sent copies of the accounts to many of his friends

and acquaintances, and to prominent persons throughout Europe.

Some of these people published his

accounts (1502, 1504) in the original Latin, and in translations to

vernacular. In 1507, the German cartographer Martin Waldseemuller republished these accounts and proposed the naming of

the new continent (north and south) after Amerigo, using the Latin

feminized form of America, to follow the example of Europa and Asia.

I report, here below, two of Amerigo's letters.

The others reported in the source book are very repetitive.

The letters are depressing when read

today, with our sensibilities. Amerigo and his fellow

travelers become increasingly jaded and callous to the indigenous

people. Any life that is not a 'Christian' male is not valued.

They enslave locals and ship them back to Europe for profit, or as

curiosities. They scrounge anything of wealth from the local

tribes, fight and kill locals sometimes just for the pleasure of

fighting, and capture many animals to ship back to Europe just for

the fun of it.

Source: C. Edwards Lester's

book of 1853 The Life and Voyages of

Americus Vespucius

Martin

Waldseemüller's 1513 edition of Ptolemy was a landmark work that

contributed to major advances in both Renaissance geography and map

printing. Published by Johann Schott in Strassburg, it depicts for the

first time in an atlas format the newly discovered continents of North

and South America connected by a coastline. (Atlas Collection, U.

S. Library of Congress) If you wish to remain on my site, here is Martin

Waldseemuller's map showing the Islands that Columbus discovered, and

coastline from both South, Central and North America. Everything

is certainly not to scale, as the Island of Hispaniola (today's Haiti

and the Dominican Republic) is nearly in the middle of the Atlantic

Ocean! And Cuba is HUGE!

The first voyage was along the coast of today's

Guyana and Venzuela, and then to Hispaniola, the island Haiti and

the Dominican Republic share today. The second voyage was along Brazil's coastline,

and depending on the accounts you believe, continuing on to

Argentina's coastline, some say to the bottom of the continent.

First Letter, about the First Voyage, to Piero

Soderini, head of Florence’s republican government:

…

King Ferdinand of Castile had ordered four ships

to go in search of new lands, and I was selected by his highness to

go in that fleet, in order to assist in the discoveries. We sailed

from the port of Cadiz on the tenth day of May, A. D. 1497, and

steering our course through the great Western Ocean, spent eighteen

months in our expedition, discovering much land, and a great number

of islands, the largest part of which were inhabited.

…

The first land we made was that of the Fortunate

Islands, which are now called the Grand Canaries, situated in the

Western Ocean, as far as the habitable world was supposed to extend,

being located in the third climate, where the North Pole is elevated

twenty-seven and a half degrees above the horizon, and distant from

the city of Lisbon (where this letter was written) two hundred and

eighty leagues. Having arrived here, with south and southerly winds,

we tarried eight days, taking in wood and water and other

necessaries, when, having offered up our prayers, we weighed anchor

and set sail, steering a course west by south.

We sailed so rapidly, that at the end of

twenty-seven days we came in sight of land, which we judged to be a

continent, being about a thousand leagues west of the Grand

Canaries, and within the Torrid Zone, as we found the North Pole at

an elevation of six degrees above the horizon, and our instruments

showed it to be seventy-four degrees farther west than the Canary

Islands. Here we anchored our ships at a league and a half from the

shore; and, having cast off our boats, and filled them with men and

arms, proceeded at once to land.

[ed. In the Torrid Zone, also known as the Tropics, the sun is

directly overhead at least once during the year - at the edges of

the tropics this occurs at the summer solstice, and over the

equator, at the equinoxes. This is the hottest part of the

earth, and there are two annual seasons: a dry and a wet. The

Torrid Zone includes most of Africa, southern India, southern Asia,

Indonesia, New Guinea, northern Australia, southern Mexico, Central

America and northern South America, and it is here that Vespucci

landed.]

Before we landed we were much cheered by the

sight of many people rambling along the shore. We found that they

were all in a state of nudity, and they appeared to be afraid of us,

as I supposed from seeing us clothed, and of a different stature

from themselves. They retreated to a mountain, and, notwithstanding

all the signs of peace and friendship we could make, we could not

bring them to a parley with us; so, as the night was coming on and

the ships were anchored in an insecure place, by reason of the coast

being exposed, we agreed to leave there the next day, and go in

search of some port or bay where we could place our ships in safety.

We sailed along the coast with a northwest wind,

always keeping within sight of land, and continually seeing people

on shore; and having sailed two days, we found a very safe place for

the ships, and anchored at half a league from the land, and the same

day we landed in the boats forty men leaping on shore in good order. The people of the country, however, appeared very shy of us, and for

some time we could not sufficiently assure them to induce them to

come and speak with us; but at length we laboured so hard, in giving

them some of our things, such as looking- glasses, bells, beads, and

other trifles, that some of them acquired confidence enough to come

and treat with us for our mutual peace and friendship. Night coming

on, we took leave of them and re turned to our ships.

The next day, as the dawn appeared, we saw on the

shore a great number of men, with their wives and children; we

landed, and found that they had all come loaded with provisions and

materials, which will be described in the proper place. Before we

reached the land, many of them swam to meet us, the length of a bow

shot into the sea (as they are most excellent swimmers), and they

treated us with as much confidence as if we had had inter course

with them for a long time, which gratified us much.

All that we know of their life and manners is,

that they go entirely naked, not having the slightest covering

whatever; they are of middling stature, and very well proportioned ;

their flesh is of a reddish colour, like the skin of a lion, but I

think that if they had been accustomed to wear clothing, they would

have been as white as we are. They have no hair on the body, with

the exception of very long hair upon the head and the women

especially derive much beauty from this: their countenances are not

very handsome, as they have large faces, which might be compared

with those of the Tartars: they do not allow any hair to grow on

the eyelids or eyebrows, or any other part of the body, excepting

the head, as they consider it a great deformity. Both men and women

are very agile and easy in their persons, and swift in walking or

running; so that the women think nothing of running a league or two,

as we many times beheld, having, in this particular, greatly the

advantage of us Christians.

They swim incredibly well, the women better than

the men, as we have seen them many times swimming without any

support, fully two leagues at sea. Their arms are bows and arrows beautifully wrought, but unfurnished with iron or any other hard

metal, in place of which they make use of the teeth of animals or

fish, or sometimes substitute a slip of hard wood, made harder at

the point by fire. They are sure marksmen, who hit wherever they

wish, and in some parts the women also use the bow with dexterity.

They have other arms, such as lances and staves, with heads finely

wrought. When they make war they take their wives with them, not

that they may fight, but because they carry their provision behind

them; a woman frequently carrying a burden on her back for thirty

or forty leagues, which the strongest man among them could not do,

as we have many times witnessed.

These people have no captains, neither do they

march in order, but each one is his own master ; the cause of their

wars is not a love of conquest or enlarging their boundaries,

neither are they in cited to engage in them by inordinate covetousness, but from ancient enmity which has existed between them in

times past; and having been asked why they made war, they could give

us no other reason, than that they did it to avenge the death of

their ancestors. Neither have these people kings nor lords, nor do

they obey any one, but live in their own entire liberty, and the

manner in which they are incited to go to war, is this: when their

enemies have killed or taken prisoners any of their people, the

oldest relative rises and goes about proclaiming his wrongs aloud,

and calling upon them to go with him and avenge the death of his

relation. Thereupon they are moved with sympathy, and make ready for

the fight.

They have no tribunals of justice, neither do

they punish malefactors; and what is still more astonishing, neither

father nor mother chastises the children when they do wrong ; yet,

astounding as it may seem, there is no strife between them, or, to

say the least, we never saw any. They appear simple in speech, but

in reality are very shrewd and cunning in any matter which interests

them. They speak but little, and that little in a low tone of voice,

using the same accentuation that we use, and forming the words with

the palate, teeth, and lips, but they have a different mode of

diction. There is a great diversity of languages among them,

inasmuch that within every hundred leagues we found people who could

not understand each other. Their mode of life is most barbarous;

they do not eat at regular intervals and as much as they wish at

stated times, but it is a matter of indifference to them, whether

appetite comes at midnight or mid-day, and they eat upon the ground

at all hours, without napkin or table-cloth, having their food in

earthen basins, which they manufacture, or in hah* gourd shells.

They sleep in nets of cotton, very large, and

suspended in the air, and although this may seem rather a bad way of

sleeping, I can vouch for the fact, that it is extremely pleasant,

and one sleeps better thus, than on a mattress. They are neat and

clean in their persons, which is a natural consequence of their

perpetual bathing.

We are not aware that these people have any laws. Neither are they like Moors or Jews, but are worse than Gentiles and

Pagans, because we have never seen them offer any sacrifice, and

they have no houses of prayer. From their voluptuous manner of life,

I consider them Epicureans. Their dwellings are in communities, and

their houses are in the form of huts, but strongly built, with very

large trees, and covered with palm leaves, secure from wind and

storms; and in some places they are of such great length and breadth

that in a single house we found six hundred people, and we found

that the population of thirteen houses only amounted to four

thousand. They change their location every seven or eight years,

and on being asked why they did so, they said that it was on account

of the intense heat of the sun upon the soil, which by that time

became infected and corrupted with filthiness, and caused pains in

their bodies, which seemed to us very reasonable.

The riches of these people consist in the

feathers of birds of the most magnificent colours, of pater nosters,

which they fabricate of fish bones, of white or green stones, with

which they decorate the cheeks, lips, and ears, and of many other

things which are held in little or no esteem with us. They carry on

no commerce, neither buying nor selling, and, in short, live

contentedly with what nature gives them. The riches which we esteem

so highly in Europe and other parts, such as gold, jewels, pearls,

and other wealth, they have no regard for at all, and make no effort

to obtain any thing of this kind which exists in their country. They

are liberal in giving, never denying one any thing, and, on the

other hand, are just as free In asking. The greatest mark of friend

ship they can show, is to offer you their wives and daughters, and

parents consider themselves highly honoured by an acceptance of this

mark of favour.

In case of death, they make use of various

funeral obsequies. Some bury their dead with water and provisions

placed at their heads, thinking they may have occasion to eat, but

they make no parade in the way of funeral ceremonies. In some

places, they have a most barbarous mode of interment, which is thus: when one is sick or infirm, and nearly at the point of death, his

relatives carry him into a large forest, and there attaching one of

their sleeping hammocks to two trees, they place the sick person in

it, and continue to swing him about for a whole day. and when night

comes, after placing at his head water and other pro visions

sufficient to sustain him for five or six days, they return to their

village. If the sick person can help himself to eat and drink, and

recovers sufficiently to be able to return to the village, his

people receive him again with great ceremony; but few are they who

escape this mode of treatment; most of them die without being

visited, and that is their only burial.

They have various other customs which, to avoid

prolixity, are not here mentioned. They use in their diseases

various kinds of medicines, so different from any in vogue with us,

that we were astonished that any escaped. I often saw, for in

stance, that when a person was sick with a fever, which was

increasing upon him, they bathed him from head to foot with cold

water, and then making a great fire around him, they made him turn

round within the circle for about an hour or two. until they

fatigued him, and left him to sleep. Many were cured in this way.

They also observe a strict diet, eating nothing for three or four

days ; they practise bloodletting, but not on the arm, unless in the

armpit; but generally they take blood from the thighs and haunches,

or the calf of the leg. In like manner they excite vomiting with

certain herbs, which they put into their mouths, and they use many

other remedies, which it would be tedious to relate.

Their blood and phlegm is much disordered on

account of their food, which consists mainly of the roots of herbs,

of fruit and fish. They have no wheat or other grain, but instead,

make use of the root of a tree, from which they manufacture flour,

which is very good, and which they call Huca; the flour from another

root is called Kazabi. and from another, Ignami. They eat little

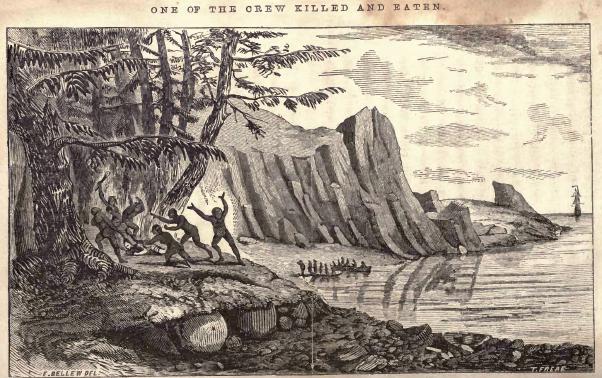

meat except human flesh, and you will notice that in this particular

they are more savage than beasts, because all their enemies who are

killed or taken prisoners, whether male or female, are devoured with

so much fierceness, that it seems dis gusting to relate, much more

to see it done, as I with my own eyes have many times witnessed this

proof of their inhumanity. Indeed, they mar- veiled much to hear us

say that we did not eat our enemies.

And your Excellency may rest assured that their

other barbarous customs are so numerous that it is impossible herein

to describe all of them. As in these four voyages I have witnessed

so many things at variance with our own customs, I pre pared myself

to write a collection, which I call "The Four Voyages," in which I

have related the major part of the things which I saw, as clearly as

my feeble capacity would permit. This work is not yet published,

though many advise me to publish it. In it every thing will appear

minutely, therefore I shall not enlarge any more in this letter,

because in the course of it we shall see many things which are

peculiar. Let this suffice for matters in general.

In this commencement of discoveries we did not

see any thing of much profit in the country, owing, as I think, to

our ignorance of the language, except some few indications of gold.

In whatever relates to the situation and appearance of the country

we could not have succeeded better. We concluded to leave this place

and go onward, and having unanimously come to this resolution, we

coasted along near the land, making many stops, and holding

discourses with many people, until after some days we came into a harbour, where we fell into very great danger, from which it pleased

the Holy Spirit to deliver us.

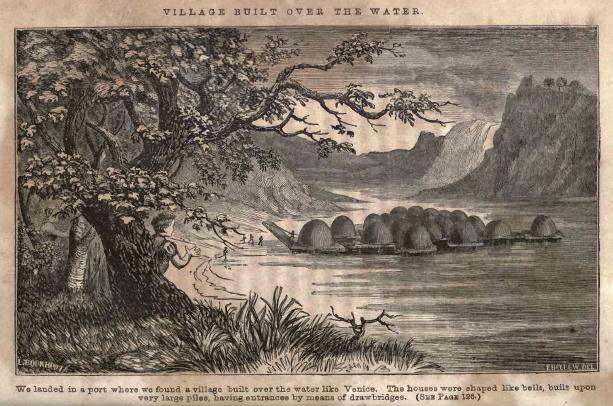

It happened in this manner. We landed in a port

where we found a village built over the water, like Venice. There

were about forty-four houses, shaped like bells, built upon very

large piles, having entrances by means of drawbridges [ed. The

natives called this place Coquibacoa: it is the modem Venezuela], so

that by laying the bridges from house to house, the in habitants

could pass through the whole. When the people saw us, they appeared

to be afraid of us, and to protect themselves, suddenly raised all

their bridges, and shut themselves up in their houses. While we

stood looking at them and wondering at this proceeding, we saw

coming toward us by sea about two and twenty canoes, which are the

boats they make use of, and are carved out of a single tree. They

came directly toward our boats, appearing to be astonished at our

figures and dresses, and keeping at a little distance from us. This

being the case, we made signals of friendship, to induce them to

come nearer to us, endeavouring to reassure them by every token of

kindness; but seeing that they did not come, we went toward them.

They would not wait for us, however, but fled to the land, making

signs to us to wait, and giving us to understand that they would

soon return.

They fled directly to a mountain, but did not

tarry there long, and when they returned, brought with them sixteen

of their young girls, and entering their canoes, came to our boats

and put four of them into each boat, at which we were very much

astonished, as your Excellency may well imagine. Then they mingled

with their canoes among our boats, and we considered their coming to

speak to us in this manner, to be a token of friendship. Taking this

for granted, we saw a great crowd of people swimming toward us from

the houses, without any suspicion. At this juncture, some old women

showed themselves at the doors of the houses, wailing and tearing

their hair as if in great distress. From this we began to be

suspicious, and had immediate recourse to our weapons, when suddenly

the girls, who were in our boats, threw themselves into the sea, and

the canoes moved away, the people in them assailing us with their

bows and arrows. Those who came swimming toward us brought each a

lance, concealed as much as possible under the water.

Their

treachery being thus discovered, we began not only to defend

ourselves, but to act severely on the offensive. We overturned many

of their canoes with our boats, and making considerable slaughter

among them, they soon abandoned the canoes altogether and swam to

the shore. Fifteen or twenty were killed and many wounded on their

side, while on ours five were slightly wounded, all the rest

escaping by favour of Divine Providence, and these five being

quickly cured. We took prisoners two of their girls and three men,

and on entering their houses found only two old women and one sick

man. We took from them many things of little value, but would not

burn their dwellings, being restrained by conscientious scruples.

Returning to our boats and thence to our ships, with five prisoners,

we put irons on the feet of each, excepting the young females, yet

when night came, the two girls and one of the men escaped in the

most artful manner in the world.

These events having occurred, the

next day we concluded to depart from the port and proceed further.

Keeping our course continually along the coast, we at length came to

anchor at about eighty leagues distance from the place we had left,

and found another race of people, whose language and customs were

very different from those we had seen last. We determined to land,

and while proceeding in our boats, we saw standing on the shore a

great multitude, numbering about four thousand people. They did not

wait to receive us, but fled precipitately to the woods, abandoning

their things. We leaped ashore, and taking the way which led to the

wood, found their tents within the space of a bow-shot, where they

had made a great fire, and two of them were cooking their food,

roasting many animals and fish of various kinds.

We noticed that they were roasting a certain

animal that looked like a serpent; it had no wings, and was so

filthy in appearance, that we were astonished at its deformity. As

we went through their houses or tents, we saw many of these serpents

alive. Their feet were tied, and they had a cord round their snouts,

so that they could not open their mouths, as dogs are some times

muzzled, so that they may not bite. These animals had such a savage

appearance, that none of us dared to turn one over, thinking they

might be poisonous. They are about the size of a kid. about the

length and a half of a man s arm, having long coarse feet armed with

large nails. Their skin is hard, and they are of various colours.

[ed. Alligators/crocodiles] They have the snout and face of a

serpent, and from the nose there runs a crest, passing over the

middle of the back to the root of the tail. We finally concluded

that they were serpents, and poisonous; and, nevertheless, they were

eaten.

We found that this people made bread of small

fish which they caught in the sea. by first boiling them, then

kneading together and making a paste of them, which they baked upon

the hot coals ; we tried it, and found it good. They have so many

other kinds of eating, chiefly of fruits and roots, that it would be

very tedious to describe them minutely. Seeing, then, that the

people did not re turn, we resolved not to meddle with or take away

any of their things, in order to reassure them; and, having left in

their tents many of our own things, in places where they might be

seen, returned to our ships for the night. Early the next morning we

saw a great number of people on the shore, and landed. Though they

seemed fearful of us, they were sufficiently confident to treat with

us, and gave us all that we asked of them. Finally they became very

friendly; told us that this was not their place of dwelling, but

that they had come there to carry on their fishery. They invited us

to go to their villages, because they wished to receive us as

friends their amicable feelings toward us being much strengthened by

the circumstance of our having the two prisoners with us, who were

their enemies. They importuned us so much, that, having taken

counsel, twenty-three of us Christians concluded to go with them,

well prepared, and with firm resolution to die manfully, if such was

to be our fate.

After we had remained here three days, we

accordingly started with them for a journey inland. Three leagues

from the shore we arrived at a tolerably well-peopled village, of a

few houses- there not being over nine where we were received with BO

many and such barbarous ceremonies, that no pen is equal to the task

of describing them. There was dancing and singing, and weeping

mingled with rejoicing, and great feasting. Here we staid for the

night, when they offered us their wives, and solicited us with such

urgency, that we could not refrain. After having passed the night

and half of the next day, an immense number of people visiting us

from motives of curiosity the oldest among them begging us to go

with them to other villages, as they desired to do us great honour

we determined to proceed still further inland. And it is impossible

to tell how much honour they did us there. We visited so many

villages, that we spent nine days hi the journey; having been so

long absent, that our companions in the ships began to be uneasy on

our account.

Being now about eighteen leagues inland, we de

liberated about returning. On our return, we were accompanied by a

wonderful number, of both sexes, quite to the seashore; and when any

of us grew weary with walking, they carried us in their hammocks

much at our ease; in passing rivers, which were numerous and quite

large, they conveyed us over with so much skill and safety, that we

were not in the slightest danger. Many of them were laden with the

presents they had made us, which they transported in hammocks. These

consisted in very rich plumage, many bows and arrows, and an

infinite number of parrots of various colours. Others brought loads

of provisions and animals. For a greater wonder. I will in form your

Excellency, that when we had to cross over a river, they carried us

on their backs.

Having arrived at the sea, and entered the boats

which had come on shore for us, we were astonished at the crowd

which endeavoured to get into the boats to go to see our ships; they

were so overloaded that they were oftentimes on the point of

sinking. We carried as many as we could on board, and so many more

came by swimming, that we were quite troubled at the multitude on

board, although they were all naked and unarmed. They were in great

astonishment at our equipments and implements, and at the size of

our ships.

Here quite a laughable occurrence took place at their

expense. We concluded to try the effect of discharging some of our

artillery, and when they heard the thundering report, the greater

part of them jumped into the sea from fright, acting like frogs

sitting on a bank, who plunge into the marsh on the approach of any

thing that alarms them. Those who remained in the ships were so

timorous that we repented of having done this. However, we reassured

them by telling them that these were the arms with which we killed

our enemies. Having amused themselves in the ships all day, we told

them that they must go, as we wished to depart in the night. So they

took leave of us with many demonstrations of friendship and

affection, and went ashore.

I saw more of the manners and customs of these

people, while in their country, than I wish to dwell upon here. Your

Excellency will notice, that in each of my voyages, I have noted the

most extraordinary things which have occurred, and compiled the

whole into one volume, in the style of a geography, and entitled it

"The Four Voyages." In this work will be found a minute description

of the things which I saw, but as there is no copy of it yet

published, owing to my being obliged to examine and correct it, it

becomes necessary for me to impart them to you herein.

This country is full of inhabitants, and contains

a great many rivers. Very few of the animals are similar to ours,

excepting the lions, panthers, stags, hogs, goats, and deer, and

even these are a little different in form. They have neither horses,

mules, nor asses, neither cows, dogs, nor any kind of domestic

animals. Their other animals, however, are so very numerous, that it

is impossible to count them, and all of them so wild, that they

cannot be employed for serviceable uses. But what shall I say of

their birds, which are so numerous and of so many species and

varieties of plumage, that it is astounding to behold them !

The country is pleasant and fruitful, full of

woods and forests, which are always green, as they never lose their

foliage. The fruits are numberless, and totally different from ours.

The land lies within the Torrid Zone, under the parallel which

describes the Tropic of Cancer, where the pole is elevated

twenty-three degrees above the horizon, on the borders of the second

climate. A great many people came to see us, and were astonished at

our features and the whiteness of our skins. They asked us where we

came from, and we gave them to understand that we came from heaven,

with the view of visiting the world, and they believed us. In this

country we established a baptismal font, and great numbers were

baptized, calling us, in their language, Carabi, which means men of

great wisdom.

The natives called this province Lariab. We left

the port, and sailed along the coast, continuing in sight of land,

until we had run, calculating our advances and retrogressions, eight

hundred and seventy leagues towards the north west, making many

stops by the way, and having intercourse with many people. In some

places we found traces of gold, but in small quantities, it being

sufficient for us to have discovered the country and to know that

there was gold in it.

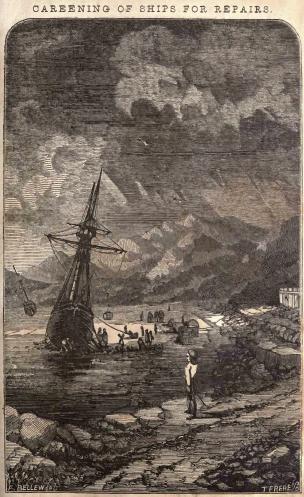

We had now been thirteen months on the voyage,

and the ships and rigging were much worn, and the men weary. So by

common consent we agreed to careen our ships on the beach, in order

to calk and pitch them anew, as they leaked badly, and then to

return to Spain. When we took this resolution, we were near one of

the best harbours in the world [ed. modern port of Mochina, on the

coast of Cumana], which we entered, and found a vast number of

people, who received us most kindly.* We made a breastwork on shore

with our boats and our casks, and placed our artillery so that it

would play over them ; then having unloaded and lightened our ships,

we hauled them to land, and repaired them wherever they needed it.

The natives were of very great assistance to us, continually

providing food, so that in this port we consumed very little of our

own. This served us a very good turn, for our provisions were poor,

and the stock so much reduced at this time, that we feared it would

hardly last us on our return to Spain. Having stayed here

thirty-seven days, visiting their villages many times, where they

paid us the highest honour, we wished to depart on our voyage.

Before we set sail, the natives complained to us,

that at certain times in the year there came from the sea into their

territory a very cruel tribe, who, either by treachery or force,

killed many of them, and eat them, while they captured others, and

carried them prisoners into their own country, and that they were

hardly able to defend themselves. They signified to us that this

tribe were islanders, and lived at about one hundred leagues

distance at sea. They narrated this to us with so much simplicity

and feeling, that we credited them, and promised to avenge their

great injuries; at which they were highly rejoiced, and many offered

to go with us. We did not wish to take them, for many reasons, and

only carried seven, on the condition that they should come back in

their own canoes, for we would not enter into obligations to return

them to their own country. With this they were contented, and we

parted from these people, leaving them very well disposed toward us.

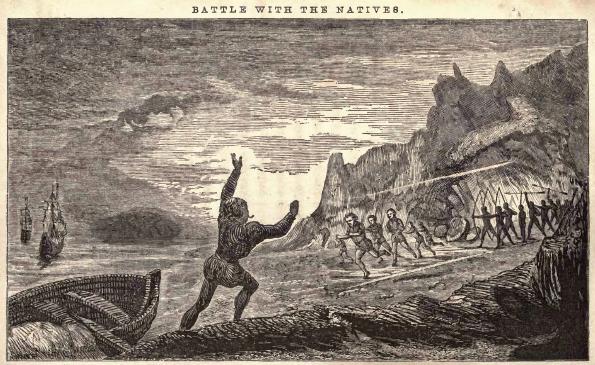

Our ships having been repaired, we set sail on

our return, taking a northeasterly course, and at the end of seven

days fell in with some islands. There were a great many of them,

some peopled, others uninhabited. We landed at one of them, where we

saw many people, who called the island Iti. Having filled our boats

with good men, and put three rounds of shot in each boat, we

proceeded toward the land, where we saw about four hundred men and

many women, all naked, like those we had seen before. They were of

good stature, and appeared to be very warlike men, being armed with

bows and arrows, and lances. The greater part of them carried staves

of a square form, attached to their persons in such a manner that

they were not prevented from drawing the bow. As we approached

within bow-shot of the shore, they all leaped into the water, and

shot their arrows at us, to prevent our landing.

They were painted with various colours, and

plumed with feathers, and the interpreters who were with us told us

that when they were thus painted and plumed they showed a wish to

fight. They persisted so much in their endeavours to deter us from

landing, that we were at last compelled to fire on them with our

artillery. Hearing the thunder of our cannon, and seeing some of

their people fall dead, they all retreated to the shore. We, having

consulted together, forty of us resolved to leap ashore, and if they

waited for us, to fight with them. Proceeding thus, they attacked

us, and we fought about two hours with little advantage, except that

our bowmen and gunners killed some of their people, and they wounded

some of ours. This was because we could not get a chance to use the

lance or the sword. We finally, by desperate exertion, were enabled

to draw the sword, and as soon as they had a taste of our arms, they

fled to the mountains and woods, leaving us masters of the field,

with many of their people killed and wounded. This day we did not

pursue them, because we were much fatigued, but returned to our

ships, the seven men who came with us being very highly rejoiced.

The next day we saw a great number of people

coming through the country, still offering us signs of battle,

sounding horns and various other instruments which they use in war,

and all painted and plumed, which gave them a strange and ferocious

appearance. Whereupon, all in the ships held a grand council, and it

was determined that since these people were resolved to be at enmity

with us, we would go to meet them, and do every thing to engage

their friendship ; but in case they would not receive it, we

resolved to treat them as enemies, and to make slaves of all we

could capture. Having armed ourselves in the best manner possible,

we immediately rowed ashore, where they did not resist our landing,

from fear, as I think, of our bombardment. We disembarked in four

squares, being fifty-seven men, each captain with his own men, and

engaged them in battle.

After a long battle, having killed

many, we put them to flight, and pursued them to a village, taking

about two hundred and fifty prisoners. We burned the village, and

returned victorious to the ships with our prisoners, leaving many

killed and wounded on their side, while on ours not more than one

died, and only twenty-two were wounded. The rest all escaped unhurt,

for which, God be thanked. We soon arranged for our departure, and

the seven men. of whom five were wounded, took a canoe from the

island, and with seven prisoners, four women and three men that we

gave them, returned to their own country, very merry and greatly

astonished at our power. We also set sail for Spain, with two

hundred and twenty-two prisoners, slaves, and arrived in the port of

Cadiz on the fifteenth day of October, 1498, where we were well

received, and found a market for our slaves. This is what happened

to me, in this my first voyage, that may be considered worth

relating! Second

Letter about the Second Voyage, to Lorenzo di Pier-Francesco de’

Medici: Your

Excellency will please to note, that, commissioned by his highness

the King of Spain, I set out with two small ships, on the 18th of

May, 1499, on a voyage of discovery to the southwest, by way of the

great ocean, and steered my course along the coast of Africa, until

I reached the Fortunate Islands, which are now called the Canaries.

After having provided ourselves with all things necessary, first

offering our prayers to God. we set sail from an island which is

called Gomera, and turning our prows southwardly, sailed twenty-four

days with a fresh wind, without seeing any land. At the

end of these twenty-four days we came within sight of land, and

found that we had sailed about thirteen hundred leagues, and were at

that distance from the city of Cadiz, in a southwesterly direction.

When we saw the land we gave thanks to God, and then launched our

boats, and, with sixteen men, went to the shore, which we found

thickly covered with trees, astonishing both on account of their

size and their verdure, for they never lose their foliage. The sweet

odour which they exhaled (for they are all aromatic) highly

delighted us, and we were rejoiced in regaling our nostrils. We

rowed along the shore in the boats, to see if we could find any

suitable place for landing, but after toiling from morning till

night, we found no way or passage which we could enter and

disembark. We were prevented from doing so by the lowness of the

land, and by its being so densely covered with trees. We concluded,

therefore, to return to the ships, and make an attempt to land in

some other spot. We

observed one remarkable circumstance in these seas. It was, that at

fifteen leagues from the land, we found the water fresh like that of

a river and we filled all our empty casks with it. Having returned

to our ships, we raised anchor and set sail turning our prows

southwardly, as it was my intention to see whether I could sail

round a point of land, which Ptolemy calls the Cape of Cattegara

(which is near the Great Bay.) In my opinion it was not far from

it, ac cording to the degrees of latitude and longitude, which will

be stated hereafter. Sailing in a southerly direction along the

coast, we saw two large rivers issuing from the land one running

from west to east, and being four leagues in width, which is sixteen

miles, the other ran from south to north, and was three leagues

wide. I think that these two rivers, by reason of their magnitude,

caused the freshness of the water in the ad joining sea. Seeing that

the coast was invariably low, we determined to enter one of these

rivers with the boats, and ascend it till we either found a suitable

landing-place or an inhabited village. Having

prepared our boats, and put in provision for four days, with twenty

men well armed, we entered the river, and rowed nearly two days,

making a distance of about eighteen leagues. We attempted to land in

many places by the way, but found the low land still continuing, and

so thickly covered with trees, that a bird could scarcely fly

through them. While thus navigating the river, we saw very certain

indications that the inland parts of the country were inhabited;

nevertheless, as our vessels remained in a dangerous place, in case

an adverse wind should arise, we concluded, at the end of two days,

to return. Here we

saw an immense number of birds, of various forms and colours; a

great number of parrots, and so many varieties of them, that it

caused us great astonishment. Some were crimson-coloured, others of

variegated green and lemon, others entirely green, and others,

again, that were black and flesh-coloured. Oh I the song of other

species of birds, also, was so sweet and so melodious, as we heard

it among the trees, that we often lingered, listening to their

charming music. The trees, too, were so beautiful, and smelt so

sweetly, that we almost imagined our selves in a terrestrial

paradise; yet not one of those trees, or the fruit of them, were

similar to the trees or fruit in our part of the world. On our way

back we saw many people, of various descriptions, fishing in the

river. Having

arrived at our ships, we raised anchor and set sail, still

continuing in a southerly direction, and standing off to sea about

forty leagues. While sailing on this course, we encountered a

current, which ran from southeast to northwest; so great was it, and

ran so furiously, that we were put into great fear, and were exposed

to great peril. The current was so strong, that the Strait of

Gibraltar and that of the Faro of Messina appeared to us like mere

stagnant water in comparison with it. We could scarcely make any

headway against it, though we had the wind fresh and fair. Seeing

that we made no progress, or but very little, and the danger to

which we were exposed, we determined to turn our prows to the

northwest. As I

know, if I remember right, that your Excellency understands

something of cosmography. I intend to describe to you our progress,

in our navigation, by the latitude and longitude. We sailed so far

to the south, that we entered the Torrid Zone, and penetrated the

Circle of Cancer. You may rest assured, that for a few days, while

sailing through the Torrid Zone, we saw four shadows of the sun, as

the sun appeared in the zenith to us at mid-day. I would say that

the sun, being in our meridian, gave us no shadow, and this I was

enabled many times to demonstrate to all the company, and took their

testimony of this fact. This I did on account of the ignorance of

the common people, who do not know that the sun moves through its

circle of the zodiac. At one time I saw our shadow to the south. at

another to the north, at another to the west, and at another to the

east, and sometimes, for an hour or two of the day, we had no shadow

at all. We

sailed so far south in the Torrid Zone, that we found ourselves

under the equinoctial line, and had both poles at the edge of the

horizon. Having passed the line, and sailed six degrees to the south

of it, we lost sight of the north star altogether, and even the

stars of Ursa Minor, or, to speak better, the guardians which

revolve about the firmament, were scarcely seen. Very desirous of

being the author who should designate the other polar star of the

firmament. I lost, many a time, my night s sleep, while

contemplating the movement of the stars around the Southern Pole, in

order to ascertain which had the least motion, and which might be

nearest to the firmament, but I was not able to accomplish it with

such bad nights as I had, and such instruments as I used, which were

the quadrant and astrolabe. I could not distinguish a star which had

less than ten degrees of motion around the firmament ; so that I was

not satisfied within myself, to name any particular one for the pole

of the meridian, on account of the large revolution which they all

made around the firmament. … It

appears to me that the poet [ed. Dante] wished to de scribe in these

verses, by the four stars, the pole of the other firmament, and I

have little doubt, even now, that what he says may be true. I

observed four stars in the figure of an almond, which had but little

motion, and if God gives me life and health, I hope to go again into

that hemisphere, and not to return without observing the pole [ed.

The Southern Cross]. In conclusion. I would remark, that we extended

our navigation so far south, that our difference of latitude from

the city of Cadiz was sixty degrees and a half, because, at that

city, the pole is elevated thirty-five degrees and a half, and we

had passed six degrees beyond the equinoctial line. … [Ed.

astronomical calculations relating to the size of the Earth, very

accurate] It

appears to me, most excellent Lorenzo, that by this voyage most of

those philosophers are controverted, who say that the Torrid Zone

can not be inhabited on account of the great heat. I have found the

case to be quite the contrary. I have found that the air is fresher

and more temperate in that region than beyond it, and that the

inhabitants are also more numerous here than they are in the other

zones, for reasons which will be given below. Thus it is certain,

that practice is of more value than theory. Thus

far I have related the navigation I accomplished in the South and

West. It now re mains for me to inform you of the appearance of the

country we discovered, the nature of the in habitants, and their

customs, the animals we saw, and of many other things worthy of

remembrance, which fell under my observation. After we turned our

course to the north, the first land we found to be inhabited was an

island, at ten degrees distant from the equinoctial line. When we

arrived at it, we saw on the seashore a great many people who stood

looking at us with astonishment. We anchored within about a mile of

land, fitted out the boats, and twenty-two men, well armed, made for

land. The people, when they saw us landing, and perceived that we

were different from themselves (because they have no beard and wear

no clothing of any description, being also of a different colour,

they being brown and we white), began to be afraid of us, and all

ran into the woods. With great exertion, by means of signs, we

reassured them, and negotiated with them. We found that they were of

a race called cannibals, the greater part, or all of whom, live on

human flesh. Your

Excellency may rest assured of this fact. They do not eat one

another, but navigating with certain barks which they call canoes,

they bring their prey from the neighbouring islands or countries

inhabited by those who are enemies, or of a different tribe from

their own. They never eat any women, unless they consider them

outcasts. These things we verified in many places where we found

similar people. We often saw the bones and heads of those who had

been eaten, and they who had made the repast admitted the fact, and

said that their enemies always stood in much greater fear on that

account. Still

they are a people of gentle disposition and beautiful stature. They

go entirely naked, and the arms which they carry are bows and

arrows, and shields. They are a people of great activity and much

courage. They are very excellent marksmen. In fine, we held much

intercourse with them, and they took us to one of their villages

about two leagues inland, and gave us our breakfast. They gave

whatever was asked of them, though I think more through fear than

affection, and after having been with them all one day, we returned

to the ships, still remaining on friendly terms with them. We

sailed along the coast of this island, and saw by the seashore

another large village of the same tribe. We landed in the boats, and

found they were waiting for us, all loaded with provisions, and they

gave us enough to make a very good breakfast, according to their

ideas of dishes. Seeing they were such kind people, and treated us

so well, we dared not take any thing from them, and made sail till

we arrived at a gulf which is called the Gulf of Paria. We anchored

opposite the mouth of a great river, which causes the water of this

gulf to be fresh, and saw a large village close to the sea. We were

surprised at the great number of people who were seen there. They

were without arms, and seemed peaceably disposed. We went ashore

with the boats, and they received us with great friendship, and took

us to their houses, where they had made very good preparations for

breakfast. Here they gave us three sorts of wine to drink, not of

the juice of the grape, but made of fruits like beer, and they were

excellent. Here also we ate many fresh acorns, a most royal fruit.

They gave us many other fruits, all different from ours, and of very

good flavour, the flavour and odour of all being aromatic. They

gave us some small pearls, and eleven large ones; and they told us

by signs, that if we would wait some days, they would go and fish

for them, and bring us many of them. We did not wish to be detained,

so with many parrots of various colours, and in good friendship, we

parted from them. From these people we learned that those of the

before-mentioned island were cannibals, and ate human flesh. We

issued from this gulf and sailed along the coast, seeing continually

great numbers of people, and when we were so disposed, we treated

with them, and they gave us every thing we asked of them. They all

go as naked as they were born, without being ashamed. If all were to

be related concerning the little shame they have, it would be

bordering on impropriety, therefore it is better to suppress it. After

having sailed about four hundred leagues continually along the

coast, we concluded that this land was a continent, which might be

bounded by the eastern parts of Asia, this being the commencement of

the western part of the continent. Because it happened often that we

saw divers animals, such as lions, stags, goats, wild hogs, rabbits,

and other land animals, which are not found in islands, but only on

the mainland. Going inland one day with twenty men, we saw a serpent

which was about twenty-four feet in length, and as large in girth as

myself. We were very much afraid of it, and the sight of it caused

us to return immediately to the sea. I oftentimes saw many ferocious

animals and large serpents. Thus

sailing along the coast, we discovered every day a great number of

people, speaking various languages. When we had navigated four

hundred leagues along the coast, we began to find people who did not

wish for our friendship, but stood waiting for us with their arms,

which were bows and arrows, and with some other arms which they use.

When we went to the shore in our boats, they disputed our landing in

such a manner that we were obliged to fight with them. At the end of

the battle they found that they had the worst of it, for as they

were naked, we always made great slaughter. Many times not more than

sixteen of us fought with two thousand of them, and in the end

defeated them, killing many, and robbing their houses. One day

we saw a great number of people, all posted in battle array to

prevent our landing. We fitted out twenty-six men well armed, and

covered the boats, on account of the arrows which were shot at us,

and which always wounded some of us before we landed. After they had

hindered us as long as they could, we leaped on shore, and fought a

hard battle with them. The reason why they had so much courage and

made such great- exertion against us, was, that they did not know

what kind of a weapon the sword was, or how it cuts. While thus

engaged in combat, so great was the multitude of people who charged

upon us, throwing at us such a cloud of arrows, that we could not

withstand the assault, and nearly abandoning the hope of life, we

turned our backs and ran to the boats. While thus disheartened and

flying, one of our sailors, a Portuguese, a man of fifty-five years

of age, who had remained to guard the boat, seeing the danger we

were in. jumped on shore, and with a loud voice called out to us, "

Children turn your faces to your enemies, and God will give you the

victory" Throwing himself on his knees, he made a prayer, and then

rushed furiously upon the Indians, and we all joined with him,

wounded as we were. On that they turned their backs to us, and began

to flee, and finally we routed them, and killed a hundred and fifty.

We burned their houses also, at least one hundred and eighty in

number. Then, as we were badly wounded and weary, we returned to the

ships, and went into a harbour to recruit, where we staid twenty

days, solely that the physician might cure us. All escaped except

one, who was wounded in the left breast.

After

being cured, we recommenced our navigation, and, through the same

cause, we often were obliged to fight with a great many people, and

always had the victory over them. Thus continuing our voyage, we

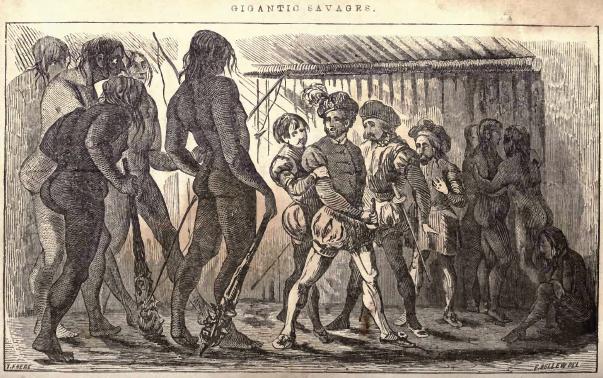

came upon an island, fifteen leagues distant from the mainland. As

at our arrival we saw no collection of people, the island appearing

favourably, we determined to attempt it, and eleven of us landed. We

found a path, in which we walked nearly two leagues in land, and

came to a village of about twelve houses, in which there were only

seven women, who were so large, that there was not one among them

who was not a span and a half taller than myself. When they saw us,

they were very much frightened, and the principal one among them,

who was certainly a discreet woman, led us by signs into a house,

and had refreshments prepared for us. We saw

such large women, that we were about determining to carry off two

young ones, about fifteen years of age, and make a present of them

to this king, as they were, without doubt, creatures whose stature

was above that of common men. While we were debating this subject,

thirty- six men entered the house where we were drinking ; they were

of such large stature, that each one was taller when upon his knees

than I when standing erect. In fact, they were of the stature of

giants in their size, and in the proportion of their bodies, which

corresponded well with their height. Each of the women appeared a

Pantastiea, and the men Antei. When they came in, some of our own

number were BO frightened that they did not consider themselves

safe. They had bows and arrows, and very large clubs, made in the

form of swords. Seeing that we were of small stature, they began to

converse with us, in order to learn who we were, and from what parts

we came. We gave them fair words, for the sake of peace, and

answered them, by signs, that we were men of peace, and that we were

going to see the world. Finally, we held it to be our wisest course

to part from them without questioning in our turn ; so we returned

by the same path in which we had come they accompanying us quite to

the sea till we went on board the ships.

Nearly

half the trees of this island are of dye-wood, as good as that of

the East. We went from this island to another, in the vicinity, at

ten leagues distance, and found a very large village the houses of

which were built over the sea, like Venice, with much ingenuity.

While we were struck with admiration at this circumstance, we

determined to go and see them; and as we went to their houses, they

attempted to prevent our entering. They found out at last the manner

in which the sword cuts, and thought it best to let us enter. We

found their houses filled with the finest cotton, and the beams of

their dwellings were made of dye-wood. We took a quantity of their

cotton and some dye-wood, and returned to the ships. Your

Excellency must know, that in all parts where we landed, we found a

great quantity of cotton, and the country filled with cotton trees.

So that all the vessels in the world might be loaded in these parts

with cotton and dye-wood. At

length we sailed three hundred leagues farther along the coast,

constantly finding savage but brave people, and very often fighting

with them, and vanquishing them. We found seven different languages

among them, each of which was not understood by those who spoke the

others. It is said there are not more than seventy-seven languages

in the world, but I say that there are more than a thousand, as

there are more than forty which I have heard myself. After

having sailed along this coast seven hundred leagues or more,

besides visiting numerous islands, our ships became greatly

sea-worn, and leaked badly, so that we could hardly keep them free

with two pumps going. The men also were much fatigued, and the

provisions growing short. We were then, according to the decision of

the pi lots, within a hundred and twenty leagues of an island called

Hispaniola, discovered by the Admiral Columbus six years before. We

determined to proceed to it, and as it was inhabited by Christians,

to repair our ships there, allow the men a little repose, and

recruit our stock of provisions; because from this island to Castile

there are three hundred leagues of ocean, without any land

intervening. In

seven days we arrived at this island, where we staid two months.

Here we refitted our ships and obtained our supply of provisions. We

after wards concluded to go to northern parts, where we discovered

more than a thousand islands, the greater part of them inhabited.

The people were without clothing, timid and ignorant, and we did

whatever we wished to do with them. This last portion of our

discoveries was very dangerous to our navigation, on account of the

shoals which we found thereabouts. In several instances we came near

being lost. We sailed in this sea two hundred leagues directly

north, until our people had become worn down with fatigue, through

having been already nearly a year at sea. Their allowance was only

six ounces of bread for eating, and but three small measures of

water for drinking, per diem. And as the ships became dangerous to

navigate with much longer, they remonstrated, saying that they

wished to return to their homes in Castile, and not to tempt fortune

and the sea any more. Whereupon we concluded to take some prisoners,

as slaves, and loading the ships with them, to return at once to

Spain. Going, there fore, to certain islands, we possessed ourselves

by force of two hundred and thirty-two, and steered our course for

Castile. In sixty-seven days we crossed the ocean, and arrived at

the islands of the Azores, which belong to the King of Portugal, and

are three hundred leagues distant from Cadiz. Here, having taken in

our refreshments, we sailed for Castile, but the wind was contrary,

and we were obliged to go to the Canary Islands, from there to the

island of Madeira, and thence to Cadiz. We were

absent thirteen months on this voyage, exposing ourselves to awful

dangers, and discovering a very large country of Asia, and a great

many islands, the largest part of them inhabited. According to the

calculations I have several times made with the compass, we have

sailed about five thousand leagues. To conclude we passed the

equinoctial line six and a half degrees to the south, and afterwards

turned to the north, which we penetrated so far, that the north star

was at an elevation of thirty-five degrees and a half above our

horizon. To the west, we sailed eighty-four distant from the

meridian of the city and port of Cadiz. We discovered immense

regions, saw a vast number of people, all naked, and speaking

various languages. On the land we saw numerous wild animals, various

kinds of birds, and an infinite quantity of trees, all aromatic. We

brought home pearls in their growing state, and gold in the grain ;

we brought two stones, one of emerald colour and the other of

amethyst, which was very hard, and at least half a span long, and

three fingers thick. The sovereigns esteem them most highly, and

have preserved them among their jewels. We brought also a piece of

crystal, which some jewellers say is beryl, and, according to what

the Indians told us, they had a great quantity of the same ; we

brought fourteen flesh- coloured pearls, with which the queen was

highly delighted; we brought many other stones which appeared

beautiful to us, but of all these we did not bring a large quantity,

as we were continually busied in our navigation, and did not tarry

long in any place. When we

arrived at Cadiz, we sold many slaves, finding two hundred remaining

to us, the others, completing the number of two hundred and thirty-

two, having died at sea. After deducting the expense of

transportation, we gained only about five hundred ducats, which,

having to be divided into fifty-five parts, made the share of each

very small. However, we contented ourselves with life, and rendered

thanks to God, that during the whole voyage, out of fifty-seven

Christian men, which was our number, only two had died, they having

been killed by the Indians. … I have

had two quartan agues [Ed. Fevers, malaria-like] since my return,

but I hope, by the favour of God, to be well soon, as they do not

continue long now, and are without chills. I have passed over many

things worthy of being remembered, in order not to be more tedious

than I can help, all which are re served for the pen and in the

memory. They

are fitting out three ships for me here, that I may go on a new

voyage of discovery; and I think they will be ready by the middle of

September. May it please our Lord to give me health and a good

voyage, as I hope again to bring very great news and discover the

island of Trapobana, which is between the Indian Ocean and the Sea

of Ganges. Afterwards I intend to return to my country, and seek

repose in the days of my old age. I shall

not enlarge any more at present, though many things have been

omitted, in part from their not being remembered at all, and in part

that I might not be more prolix than I have been. I have

resolved, most excellent Lorenzo, that as I have thus given you an

account by letter of what has occurred to me, to send you two plans

and descriptions of the world, made and arranged by my own hand and

skill. There will be a map on a plane surface, and the other a view

of the world in spherical form, which I intend to send you by sea,

in the care of one Francesco Lotti, a Florentine, who is here. I

think you will be pleased with them, particularly with the globe, as

I made one not long since for these sovereigns, and they esteem it

highly. I could have wished to have come with them personally, but

my new departure, for making other discoveries, will not allow me

that pleasure. There are not wanting in your city persons who

understand the figure of the world, and ^ho may, perhaps, correct

something in it. Nevertheless, whatever may be pointed out for me to

correct, let them wait till I come, as it may be that I shall defend

my self and prove my accuracy. I

suppose your Excellency has learned the news brought by the fleet

which the King of Portugal sent two years ago to make discoveries on

the coast of Guinea. I do not call such a voyage as that a voyage of

discovery, but only a visit to discovered lands; because, as you

will see by the map, their navigation was continually within sight

of land, and they sailed round the whole southern part of the

continent of Africa, which is proceeding by a way spoken of by all

cosmographical authors. It is true that the navigation has been very

profitable, which is a matter of great consideration here in this

kingdom, where inordinate covetousness reigns. I understand that

they passed from the Red Sea, and extended their voyage into the

Persian Gulf, to a city called Cali cut, which is situated between

the Persian Gulf and the river Indus. More lately the King of

Portugal has received from sea twelve ships very richly laden, and

he has sent them again to those parts, where they will certainly do

a profitable business if they arrive safely. May our

Lord preserve and increase the exalted state of your noble

Excellency as I desire. July 18th, 1500. Your

Excellency s humble servant,

AMERICUS VESPUCIUS. Here are some more images from the same source,

illustrating events from other letters about other voyages.

Amerigo

Vespucci

![]()

Italian Navigators Didn't Work for Italians

Why Amerigo Went to Spain

John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto)Discovered North America in 1497 (after

the Vikings in 1005)

Elena Vespucci and the Vespucci Descendents

![Thumbnail image of Martin Waldseemuller's "Cosmographiae introductio" [St. Die, 1507]](images/rat15001.jpg)

The development of both the compass (c.1200) and the mariner's

astrolabe (c1550) made sailing more accurate, and map-making

possible.

The First Voyage

The Second Voyage