Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

The kitchens in

the basement of Caterina de' Medici's French Castle Chenonceau are

wonderfully preserved, as you can see here in these images I made on

a recent visit. The butcher's block with knives and the drawer in

the bottom for blood and bits that were used for sausages. The

hooks are for hanging fowl and other meats.

Another butcher's block, well-used, with the handy

drawer underneath.

One of the hearths with cooking pots hanging, and

the table full of produce.

The bread oven with bread forms and a ready supply

of wood.

If you step back, you can see the bread paddles,

the same type that are used by pizza makers around the world.

Here you can see that the bread oven sit next to a

cooking hearth.

The sink with a pump that pumps water from the

River Cher below.

I also have on my site An Al Andalus Cookbook, or an

Anonymous Andalusían Cookbook,

as copied by a scribe in the 1400s, from texts from the 1200s, that

often were themselves transcriptions of books from the 900s.

The PDF is featured on another page on this

website, which provides more information on this book and the

recipes, which have

direct links to Sicilian cooking, and indirect links to Italian

cooking. The rest of this page refers only to the 3 Italian

books mentioned above.

There is a

wonderful book about the customs of the Middle Ages and the

Renaissance that includes many images, and tons of curious

information.

It is available to read on-line via Gutenberg Press, for free.

English

Translations Available On-Line

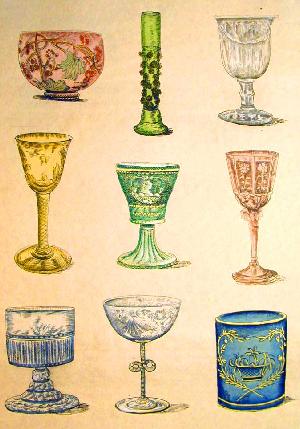

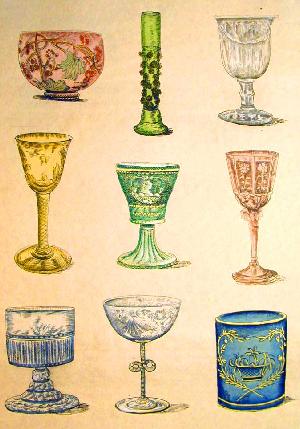

Some images from Scappi's

Book

The University of Marburg in Germany provides rough text

transcriptions (links

at bottom of page) of three ancient Italian cookbooks. I've

converted these texts into more useful indexed and edited PDF books that

you can access and download. Anonimo Toscano,

Libro

della cocina Anonimo Veneziano,

Libro

di cucina/

Libro per cuoco This

text is from the Veneto area of Italy from circa 1430. It is 29 pages

long and incorporates many of the recipes from the Toscano book.

The Italian is rich with French, Spanish and Latin influences, and

transliterations of the Venetian dialect's soft consonant

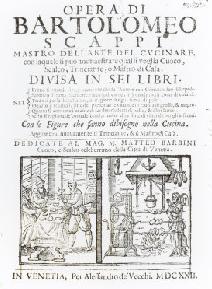

pronunciation. Later in about 1550, a

cook, Bartolomeo Scappi, put together another cookbook, which again

incorporated many of Maestro Martino's recipes, re-written.

The book was reprinted for over 100 years. (images

from the book below) (link

to scanned copy below).

I also have on my site An Al Andalus Cookbook, or an

Anonymous Andalusían Cookbook,

as copied by a scribe in the 1400s, from texts from the 1200s, that

often were themselves transcriptions of books from the 900s.

The PDF is featured on another page on this

website, which provides more information on this book and the

recipes, which have

direct links to Sicilian cooking, and indirect links to Italian

cooking. The rest of this page refers only to the 3 Italian

books mentioned above. These books are fun reads. They're written in an Italian that

is a mix of Italian and Latin and sometimes French and Spanish.

The local dialect and pronunciation is written

phonetically. For example, in the Venetian cookbook, the soft

Venetian pronunciation of 'gg' and 'ci' (friggere, braccia) in

Italian is written as 'z' and 'x' respectively (frizere, braxa).

And the soft French ç is used to signify a soft pronunciation in a

word like dolce, becoming dolçe (dolsay).

It makes it easier to understand if you know any of these languages

besides Italian.

Try reading the words aloud phonetically, and listening to them.

They often sound like modern Italian, but are just written with a

different spelling. The spellings vary. The masculine and feminine of the words

vary. And the words vary sometime even within one book. This

is because languages were not yet categorized and documented by

national governments and policed by language departments, and most

importantly, each book was not

the work of one author. It's best to think of the books as notebooks contributed to on

loose sheets of parchments by visiting or permanent cooks in

large feudal-style or manor house kitchens. That's why most of them are

attributed to an 'Anonymous' cook from a general region of Italy,

and include instructions at the end of many recipes to 'now serve

the dish to the Lord of the Manor' (da' al Signore). They were eventually gathered together, edited, and printed,

resulting in these cookbooks.

The regional distinctions of the anonymous authors really have little meaning. Each

book cites recipes from other European regions and even from North

Africa. Actually, many of the recipes have similar versions in

North African cooking, and many of the ingredient names are

bastardizations of North African words. This was not a time of

the modern nation-state, but instead it was a feudal period that evolved into Prince-run-states,

some enlightened by the Italian Renaissance (Rinaciamento). People, especially

tradesmen like master chefs, were very mobile. Even

Leonardo da Vinci offered his services to the chef of Ludovico di

Sforza in Milan to make his banquets more exciting with pyrotechnics

and robots, as described in this book.

Reading the books, you discover

not just traditional dishes and variations you might never have

imagined, but also things about the time period, the social

history. For

example:

Spices are used individually in the recipes, but most often, similar to all European cooking from that time,

they use spice mixes called 'sweet

spices' and 'strong spices', and sometimes 'fine spices'. These mixes are most comparable to today's

spice mixes for stuffing, pumpkin pie, pasta, etc. and the Asian 5 and 7 spice mixes,

for example, and the various curry spice mixes throughout

India.

Food back then was often strong and pungent, or sweet and sour, so

the recipes call for lots of spices, and suggest the cook cater to

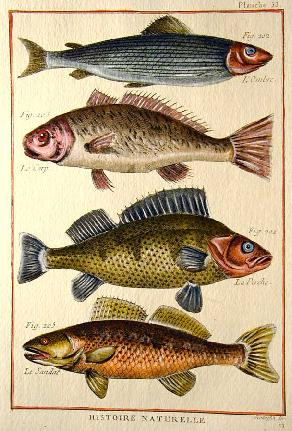

the tastes of the Lord of the Manor, his patron. The mixes usually included various combinations of: In some parts of Europe, the sweet mix includes sugar,

but not in the Italian recipes. To give an idea of the mixes,

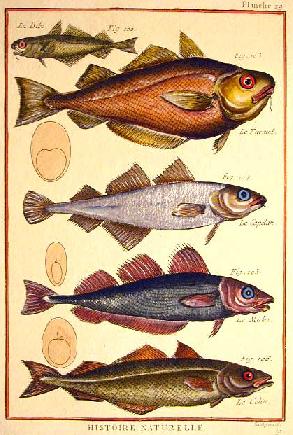

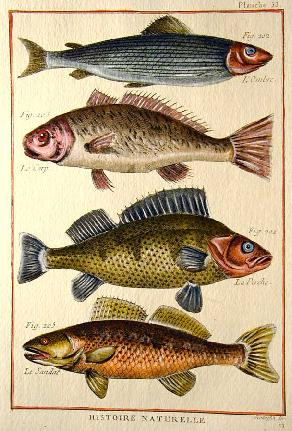

here are translations of the recipes from the Venetian cookbook. Sweet Spice Mix Sweet spice mix for many things good and fine.

The best sweet, fine spice mix that you can make if you want it for

lampreda (ed. eel-like fish) in a crust and for other good fresh water

fish that you make in a crust and for making good broth and good

flavors/sauces. Take a quarter ounce of cloves and an ounce of

good ginger and take an ounce of ground cinnamon and take the same

amount of bay/laurel leaf and grind together all these spices as

finely as you wish. And if you want to make more, take the

things in the same proportions, and it is wonderfully good. Strong Spice Mix Black and strong spices for much flavor/sauces.

Take an eighth of an ounce of cloves and two ounces of pepper and

take the same amount of long pepper and two ounces of nutmeg and

grind them all together into your spice mix. Fine Spice Mix Fine spice mix for many things. Take one ounce of pepper and one of cinnamon and

one of ginger and an eighth of an ounce of cloves and one quarter of

saffron. Spice mixes, just like in India today, also were combined to

create not just a certain flavor in food, but also a certain color:

white, golden brown, red, and green, for example.

Herbs that we know today appear as well, like: And these herbs were often combined in soups and sauces.

Some of the recipes call them herbe odorifiche, aromatic

herbs. They were either grown in the cook's garden, bought

from a farmer's market, or collected from the fields, wild herbs,

herbe selvatiche.

The earliest pizza recipe in the cookbooks is one made from

sliced rounds of bread. The traditional loaf, still sold

throughout Italy (and Spain and Greece), is a large, round loaf of

about 1 kilo (2 lbs.). It is turned on end and cut into circles,

a finger thick. The round is then fried in a pan in oil and

lard, and seasoned with herbs and cheese. Ravioli (raffioli) are mentioned in the earliest

cookbook, and the recipe is repeated in the other books.

The ravioli (the dough made with flour and water) are filled with all kinds of things,

both sweet and savory (often a mincemeat),

and either boiled in broth or fried, and sometimes topped with sugar.

Today in Italy ravioli is also used as a generic term for a

filled pasta.

Lasagna shows up early too, and is just a flat, thin pasta of

flour and water cooked in broth and topped with

extra animal fat for good measure. But there is an early

recipe for a baked dish that layers a crust or pasta (pastello)

with other ingredients, which resembles today's

lasagna. In Maestro Martino's book, which is the latest of the three

books, there are more recipes for pastas, including sun-dried

pastas that could be stored for up to 3 years, and when cooked,

should be cooked for 1 to 2 hours! Tagliatelle: Martino calls it maccaroni

romaneschi, but it is the same as today's tagliatelle, even to

the point of telling us we can cook them in the nest form or

separated into string form. The pasta is rolled around a

bastone, club, which today in Italian is called a matarello,

the the rolling pin is removed and the pasta is cut. He says

to cook it in broth or water, then serve it seasoned with butter,

cheese and sweet spice mix. Interestingly, today in Italy you

can buy a tagliatelle that is twisted, and called maccheroni.

And in Italy maccheroni is used as a generic term for pasta. Spaghetti: Martino calls this triti or

formentine, but as described it is recognizable as today's

spaghetti or linguini. He says to make it like the

tagliatelle, but cut it much thinner. It's served up the same

as tagliatelle. Bucatoni: Martino call them maccaroni siciliani,

and explains that you make a flour pasta that includes egg white and

rose water. Then you roll strips

of the pasta

as long as your hand, around a wire as thick as a piece of straw (spagho),

then remove the wire. This makes a thick, hollow pasta that

today is called generally bucatoni. He says to dry them in the

sun. I actually call them fire-hoses, because that is what

they remind me of. They are very heavy, and need to be cooked

a long time, but perhaps not the 2 hours that Martino recommends! Vermicelli: This soup pasta is the same as today's

soup pasta called vermicelli (little worms, or larvae).

Martino says to cook them for 1 hour, and to color the dish yellow

with saffron, unless you cooked them in milk.

Some quirks you come across include: Some common ingredients are:

Coloring the food was common. The aesthetics of the

dishes appear to be as important to the cooks then as they do to

chefs today. Instructions on how to color food blue, black,

yellow, red, etc. appear in the cookbooks, as do suggestions for

special presentations for banquets religious festivals.

For example:

Interestingly, considering the recent interest in Super Foods

that bring healthful benefits, is that each cookbook includes

recipes for the infirm. The problem is detailed in the

recipe title: constipation, can't urinate, has a cold, is

weak, is gouty, stones, weak liver... Medicines in those days were not synthetic pharmaceuticals.

Instead, medicines were herbs, spices, roots, leaves, and foods.

So: Besides health tips and recipes, there are also helpful tips

and tricks on how to: If you'd like, you can visit my page on the

History of Italian Food

and Recipes.

St. Mark's Square

in the 1860s And writer William Dean Howells lived in Venice from

1861 to 1865 as U.S. Consul under President Lincoln. I have

prepared a

And the Castello Banfi winery site in Montalcino,

Tuscany has a page I like that tells about the If you are interested in knowing more about Medieval

and Renaissance cooking, visit this

wonderful site.

Here are some links to books available from Amazon.com, if you wish

to read more about the history of Italian cooking.

The first two links are to English translations of Maestro

Martino's book, including scholarly prefaces and other recipes

from the era (most likely from the other two free books I offer

above). And Scappi's Opera.

Artusi's book is a classic of modern Italian

cooking. The book on the medieval kitchen includes

Italian and French recipes from the same era as the free books I

offer, with scholarly information about the era.

The showy aspect of ancient cooking is covered in the Taylor

book as it pertains to the Sicilian cuisine from Greek times to

today, including lots of recipes. And the food of ancient

Rome in covered in the second and fourth books, including recipes you can

cook today. Then there is an ancient Neapolitan recipe book

The culinary history of all of Italy gets scholarly coverage

in the Capatti book. And Da Vinci's inventions for his

Milanese patron's chef make for entertaining reading in Dewitt's

book.

Anonimo Toscano English

Anonimo Toscano Italian Plain Text

Anonimo

Veneziano English

Anonimo Veneziano Italian Plain Text

Maestro Martino Italian Plain Text

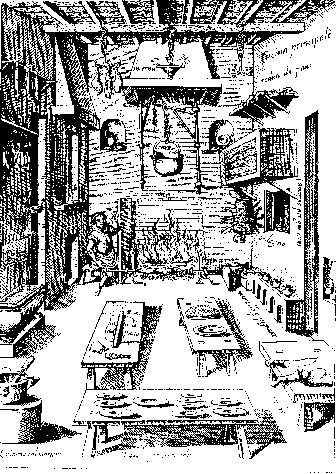

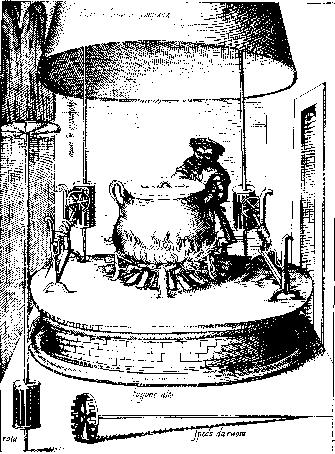

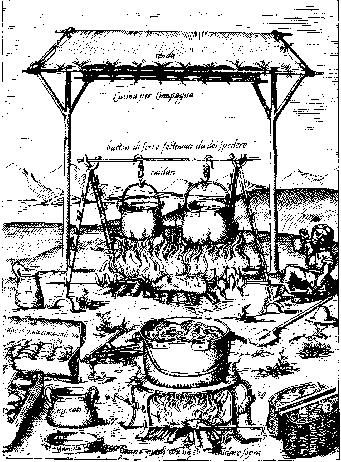

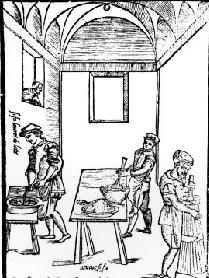

Cucina principale - Main Kitchen

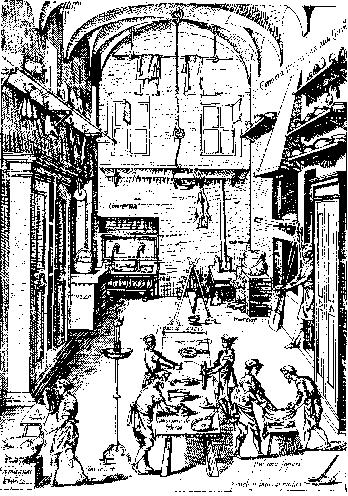

Cucina propinqua alla cucina - Pantry Kitchen

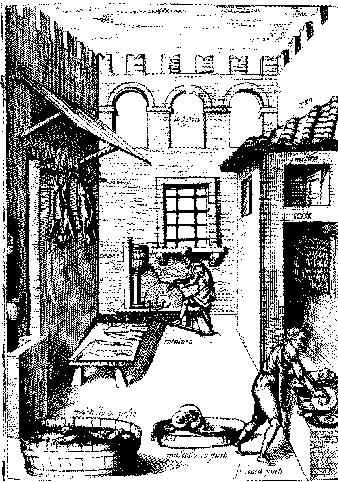

Loggia - Open-air Kitchen

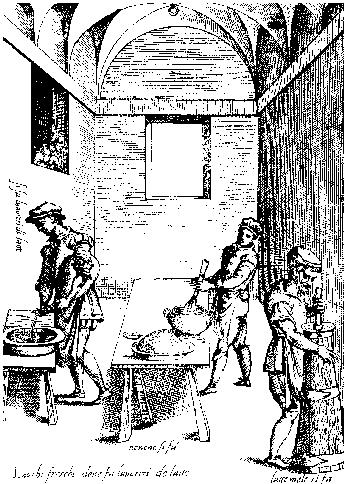

Luoghi freschi dove lavorare il latte - Cool

places where milk is worked (into butter and cheese)

Cucina fatta a campana - Kitchen in the form of a

bell

Cucina per campagna - Field Kitchen

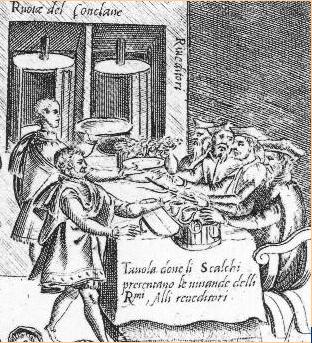

Masserizie per camera di conclave - Meals for the

Conclave Room - An image showing how the

meals were sent into the Cardinals electing the new Pope, locked in

the conclave room (now the Sistine Chapel).

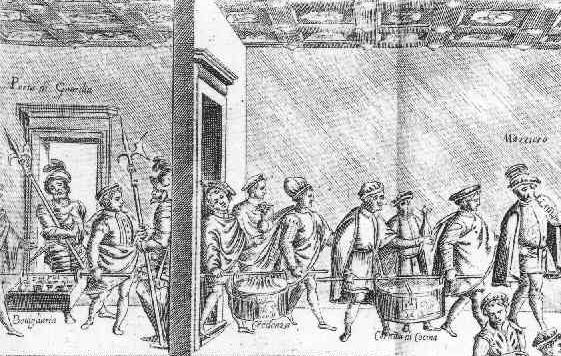

Ordine che si tiene per serviere gli Illustrissimi cardinali al

conclave - The process of serving the illustrious cardinals in the

conclave room - The procession of food had to be approved by inspectors,

who then had the food set inside the wheels beside them. Then

the wheels were turned so the food appeared on the other side, the

conclave room, at

the same time as the view from the inspector's side was blocked.

Middle Ages and Renaissance Italian Cookbooks

![]()

Manners, Customs, and Dress During the Middle Ages, and During the

Renaissance Period.

By Paul Lacroix

(Bibliophile Jacob),

Curator of the Imperial Library of the Arsenal, Paris.Illustrated with

Nineteen Chromolithographic Prints by F. Kellerhoven

and upwards of

Four Hundred Engravings on Wood.

Free On-line

This is the earliest

(circa 1380) and briefest (23 pages)

of the three books. The Italian is difficult to read if

you only know Italian because the language used has lots of Spanish

influence.

About These Books

About the Era

Spices and Herbs

Pizza and Pasta

The Ingredients

Coloring Food, and Banquets

Medicine, and Tips and Tricks

Some Other Things of Interest

From Amazon.com

English

Translations Available On-Line

Some images from

Scappi's (Platina's) book